I recently attended an Urdu workshop by Vimal Chitra, Natasha Badhwar and Raju Tai. I had signed up as soon as I saw the dates even though I was traveling. I wanted to make it work because I hadn’t been able to make time for Urdu before. Saying this feels a bit strange when Hindi is your mother tongue. I mean I have no difficulty understanding any video from Pakistan. But there are those words aren’t there, which when uttered while speaking Hindi, tempt Urdu to take a peek from behind the curtain. I mean those words whose faces we remember but names we forget. Those that when used now makes people think ‘Ah he’s trying to speak Urdu’. If you had asked her, my Nani would have said she spoke Hindi but Urdu may have objected because she used those words without the effort of thinking about them.

When she got married, compatibility was never a criteria in arranging them and it led to all manner of differences emerging between a couple but one thing that was usually the same was language. With Nana and Nani on the other hand, while their languages were similar, they were not the same. While my Nana was from Bareilly, Nani was born and raised in old Lucknow. She never had the courage to say it to him, but for her, his language was uncouth. It wasn’t just that my Nana loved his swear words, providing his children a graphic and unwitting education into the ways of the world; the rest of his language stung the Lakhnavi ear too. Nani’s side of the family was shocked to know that he used words like launda and laundiya instead of ladka and ladki for example. It was no wonder then that Nana hated his wife’s family with the exception of her brother who he inexplicably loved, maybe because he didn’t blanche every time Nana spoke.

Nani on the other hand had never used a foul word in her life. While looking at my mum’s schoolwork she would ask her what kind of harf or alphabets she is writing instead of the standard Hindi word Akshar. Pages were not panne but barkhe. And when she referred to ink as Roshnai instead of Syahi, my mother wondered who Nani was and what she was doing in this house. None of her kids who grew up in Kanpur had this vocabulary. Waving her blue plastic hand fan in Kanpur’s power-cut ridden summers, she told me the story of an old man in Lucknow who was walking in the gullies with a hunch. A cheeky youngster asked him what he was looking for.

The old man replied, “Jhukaye sar zaifi humari, javaani ko aathon pahar dhoondti hai”.

I had to ask her ye zaifi kya hai? She said budhapa. My eyes grew wide as that word became the key which unlocked the three-line story. This head that is bowed by old age is always searching for its youth. I struggled to imagine what she looked like when she was as old as I was then, coming of age around those words in the Lucknow of the 1920s and 30s. She was the last generation of upper caste Hindus who grew up with those words as this was also the time when the process of adorning Hindi and Urdu with distinct religious and political identities was reaching its zenith. On my last visit to the Residency in Lucknow, I realised that this was a process that began in 1857 and culminated in 1947.

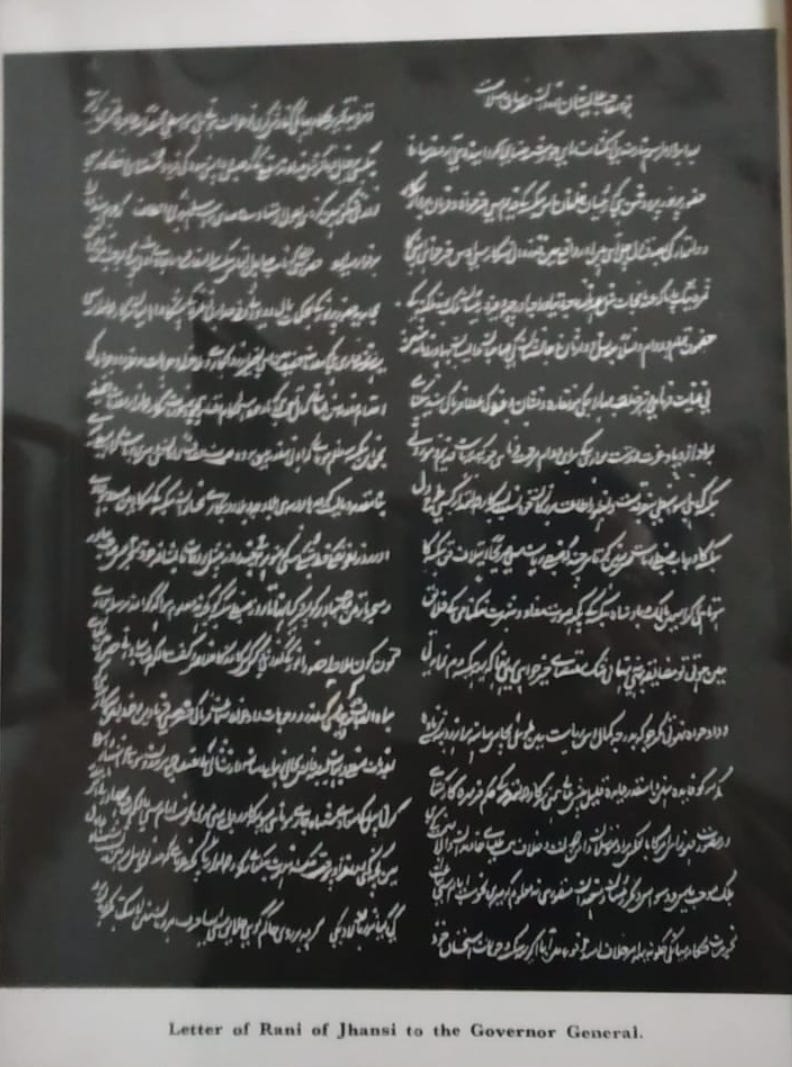

The basement in the Residency where British women and children hid during the siege in 1857 has been converted into a museum. Here, in the midst of a somewhat hagiographic representation of the rebels, I found letters that the Queen of Jhansi Lakshmi Bai had written to the British. What struck me about the letters was that even as late as 1857, an Indian ruler was writing letters to the British in Persian using the Nastaliq script. These letters were the last embers of what the historian Richard Eaton has called India’s Persianate Age. The title of his book has the dates 1000-1765 so the death throes of this age from which those words come from lasted nine decades.

It was in the nine decades after 1857 that identities of the subcontinent entered the cauldron of the Raj and emerged reforged. In the early part of that period, it was still possible for upper caste Hindu men like my Nana’s grandfather to have a name like Bakhtawar. Names like these which cut across faith were the first to go. By the end of the 19th century, in a movement spearheaded by the likes of Bhartendu Harishchandra, Hindi and Urdu, names that had been used interchangeably for a common language, were being cleaved out as distinct tongues. After all, a hundred years before that movement, Mir Taqi Mir, the greatest Urdu poet of his age had referred to his language as Hindi or Rekhta, not Urdu. The scripts were the second casualties as Hindus were encouraged to write Hindi in Devanagri and Muslims wrote Urdu in Nastaliq. Hindi’s most celebrated writer Munshi Premchand began his career writing as ‘Nawab Rai’ in Urdu. He made the shift to Hindi later because the number of people reading in Hindi were growing and he wanted a wider readership. Firaq Gorakhpuri belonged to the last generation of Urdu poets who were Hindus from UP while the Lucknow poet Josh Malihabadi chose to migrate to Pakistan despite remonstrations from Nehru to stay because he had heard Urdu’s death knell in India.

After the names and the scripts, those words were the last to go. The only script Nani knew was Devanagri. But she still grew up around those words. Her children did not have them and Nani’s own use of them diminished as she adjusted to a new normal. When they made an appearance, they drew attention to her but there were times when she had to use them. When as a toddler she had begun coming to terms with the world and had been forced to point at things, they had come to her rescue. It was through them that she had learnt of pages, alphabets, ink and old age. They couldn’t be so easily abandoned.

During the Urdu workshop, Vimal had asked each of us our favorite Urdu word and I had said Roshnai. I thought it was a beautiful word for ink; that which illuminates. Or it did, when we used it in school. Ink is becoming a part of the past that Roshnai has inhabited for longer. So I was glad I got to use and share the word during the workshop and find it in the company of favorites from other participants.

So lovely. Every 6th of December I think of another cleavage. The Lucknow I grew up in changed that day as Hindus living in the old city moved out to new Gomti-par neoliberal developments and the last vestiges of a Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb faded away. Taking everyday Urdu along with it. You essay reminded me of that time.

Beautiful Ayush,I remember you told Roshnai .

The explanation of the divorce of the two world's,your nani's world ,you have written it so vividly. Bahut khoob.